24 March 2023

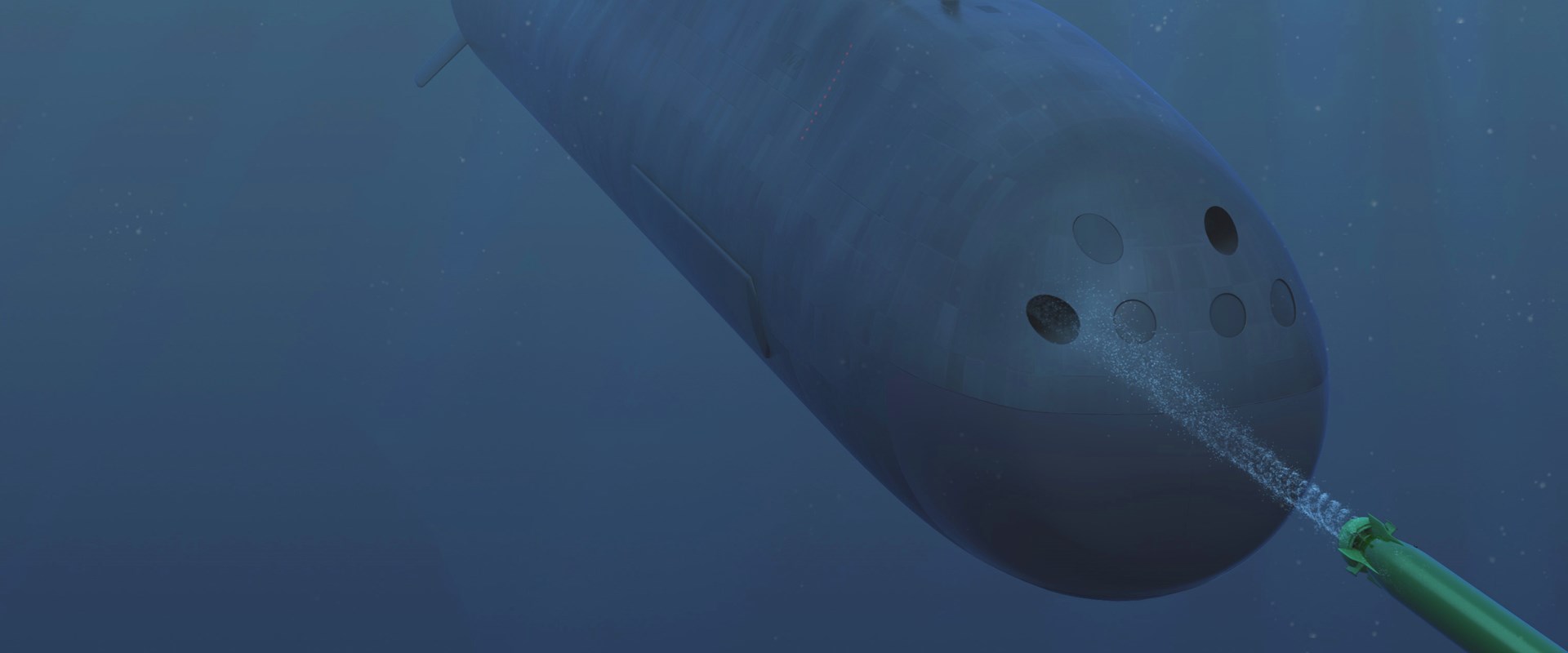

The path to Australia’s nuclear-powered submarine future has many challenges, and while some might underestimate Australia’s ability to make this transition, the challenge and the necessary solutions are doubtlessly receiving the appropriate attention. However, there is a potentially even bigger problem lurking in the shadows of the debate.

The biggest issue, and potentially the costliest long-term challenge is people. The fact that we need highly skilled people to build, operate and sustain nuclear submarines doesn’t mean they will come, and this is a conversation that needs to be in sharp focus here and now. As Australia finds itself at the start of the SSN acquisition life cycle, we are at a critical period to also deal with the parallel task of human capability acquisition.

Beyond figuring out the qualifications and technical competencies required of an SSN workforce, there are fundamental questions that need to be asked. Why would people want to join? Why would they transition from the Collins Class? Why would they stay in the submarine force and away from their friends and family for months on end when they could earn more ashore? The step change in submarine capability gives the opportunity for a step change in dealing with people and their career design.

Any attempt to implement an effective workforce strategy will need to address sound ‘organisational career management’, or simply ‘good career design’. To deploy this strategy and reap the benefits of a committed and capable workforce – the Country needs to act now.

The skills that come with operating a nuclear plant mean new challenges and new career paths. It may be simple to suggest that Australia’s future nuclear powered submarine fleet could easily be crewed in a similar way to those of the UK or US, depending on the choice of vessel, but from the Royal Australian Navy point of view it is unlikely to be that simple.

Our partners have mature systems and industries/civil services that can absorb these highly trained and well-paid individuals. This ensures that their career does not stop on departure from navy, and instead they are able to continue using their skills within the wider nuclear industry enterprise. Australia does not have a civil nuclear industry, nor is it likely that this will change in the near to medium-term.

Australia will be making a costly and long-term commitment to the development of personnel to fill critical nuclear positions. To ensure that the investment in human capability provides long-term returns, consideration needs to be given to the human element and how personnel may be retained or seamlessly transition to civilian jobs, whether in government service or wider industry being able to take on such individuals for the ongoing benefit of the nation. Australia faces a set of challenges and circumstances quite different from our established AUKUS partners which will require unique solutions.

There needs to be a particular focus on planning to avoid potential career dead-ends for those highly trained staff. The workforce problem is significant. The building up and retention of an appropriately skilled nuclear trained workforce will be as essential as the delivery of the platforms themselves. Getting this right will mean that Australia’s expensive and highly capable materiel can be operated successfully and be given the best chance to return home safely over its whole life.

Good career design is required for this to happen. By this we mean the range of policies, practices and activities undertaken by the organisation to support an individual’s professional and career development, as well as the submariner having the assurance that their skill-sets will be productive during their career and beyond. Of course, good career design isn’t just a bumper sticker, and concrete actions are needed.

We suggest this issue is addressed by first considering what underpins the complex issue involved, and by describing what we have called the Human Capability Life-cycle (HCLC). In designing a framework for good career design that can be efficient and effective both for the human and the organisation, this term needs to be intrinsically understood. We suggest that the HCLC must be considered as a Fundamental Input to Capability, where potential career dead ends are designed out. The well-established SMART work design model, developed by Australian Research Council, professor Sharon Parker, at the Future of Work Institute, is a helpful framework in this context that can underpin good career design and contribute to sustainable workforce outcomes.

The Human Capability Life-cycle as we envisage it reflects the logical nature of the Capability Life-cycle: just as materiel is underpinned by that process we are suggesting it should be that way for the workforce too. Submarine operational capability and safety is fundamentally about people. Achieving the capability objectives of the expensive materiel will almost certainly only happen with personnel who have the right training, motivation, and career prospects. Whilst it is important to get the materiel aspects right; it is perhaps the human aspects that need the greatest attention to ultimately achieve effective operational performance and sustainment, this is where good career design comes in.

Deriving well-thought through career paths early on, before people reach the major milestones in them, will pay dividends. Indeed, the development of a good career design with potentially multiple pathways, opportunities, flexibility and nationwide synergies will benefit the whole of Australia as well as the RAN. The capabilities of those who have served this country are a vital ingredient in its future prosperity – but only if that talent is managed properly across their whole HCLC. If done well it will lead to long and enduring career pathways, perhaps not solely within the RAN, and ought to be a starting point for near and long-term interest and recruitment campaigns that fulfill the recruitment need.

If the good career design that we imagine is going to be meaningful and fulfilling for the human as well as effective for the organisation it needs to have a clearly set out pathway and systems to achieve that outcome. Part of that is the avoidance of potential career dead ends by designing them out. It is this aspect that we believe needs to be intrinsically understood in attempting to design a framework for careers that will serve Australia well. In this we must consider educational needs, recruitment methods through to service retirement and beyond, and to maximise efficiencies we need to develop good career design strategies that support employees through their various and foreseeable life events.

‘Recruit the person, retain the family’, so the mantra goes, and this must be the driver, if we are to successfully underpin Australia as a nuclear submarine operating nation. Careers must contain sufficient cross-industry, multi-national and pan-government service flexibility, training and re-training, to ensure the person can have a fulfilling career that meets the needs of the organisation, the person and their family unit. This is why we see good career design as key to enabling core skills and competencies to be maintained either within the RAN nuclear engineering domain or in its supporting entities be, they specifically linked industries or other government roles. But for success there must be no doubt in the minds of policy makers that the significant through-life costs of good career design implementation are a necessary investment in Australia’s safety, success and credibility, as a nuclear operating nation.

We know from research conducted by the Foundation of Young Australians that traditional career trajectories are outdated, and it’s more likely a 15-year-old today will experience a portfolio career, potentially having 17 different jobs over 5 careers in their lifetime. Of course a Navy career could perhaps already be described as a portfolio career; the difference being there is only one employer. Good career design might mean potentially expanding that to include several differing employers, but ones that ensure the skills are maintained in the nuclear sphere. This mitigates against personnel outflow from the start, by both addressing the expectations of those we need recruit, but also by addressing what Defence itself needs from people too.

In stating these points, we are not advocating for any particular solution but merely highlighting the potential significant risks that we face in this sphere. To continually meet the design intent of the HCLC might mean that our education system needs to alter to support the requirement to deliver the multi-generational technical needs. Without a civil nuclear industry or similar analogue, then it is important to recognise that Australia may be at risk of growing generations of highly trained individuals, at great and ongoing expense, who may have very few in-country places to go to after a service career, thereby creating a huge waste of investment, perpetuating the career dead-end, and making the role potentially very unappealing and difficult to recruit into in the first place.

To illustrate the time, effort and cost elements of a nuclear engineers training pipeline we will use the UK Submarine Service’s Marine Engineering officer role as an example. With several assistant Marine Engineering Officers of both commissioned and non-commissioned personnel the size of the Marine Engineering department on a NPS is significantly larger than an SSKs.

An engineering graduate will undergo military and then employment training, and to achieve basic proficiency in the operation of the nuclear plant at sea will take an operator several years as the training works through several substantive Assistant MEO roles. This period takes the trainee through the learning required for both professional boards and validation training to meet the regulated assurance and performance levels required.

Although the example is UK-based, and regardless of the crewing system used, the US has a larger requirement for nuclear SQEP, there will be a significant cost to the crewing and training element. It is self-evident that the RAN will need to grow its workforce considerably, especially its Marine Engineering workforce. This covers the uniformed workforce point of view. But what does the wider defence industry need, and what is required for Australia’s continued development?

Ultimately there are significant benefit for all if planned good career design allows the uniformed workforce to seamlessly turn into non-uniformed staff. While there is a significant cost in planning to lose highly trained personnel to other roles, the cost of not providing those planned pathways is far higher. People will leave Navy at some point, and they are more likely to leave sooner, with less overall benefit to Australia if they can't see a long-term portfolio career ahead, that fits their current and next life stages.

We thank Australia Pacific Defence Review, Editor Kym Bergmann for publishing our article in March 2023.

Chris Greenbank is a Chartered Ergonomist and Human Factors specialist at BMT. His expertise is in Submarine human factors, HSI management and the practical application of scientific knowledge from across domains to deliver the required human factors outcomes for clients.

Katrina L. Hosszu is a Senior Researcher at the Future of Work Institute, Curtin University. She received her Master of Industrial/Organisational Psychology from the University of Western Australia. She undertakes applied research, engaging with industry and government to concurrently improve workplace practices and scientific knowledge. She has been working with Defence Science and Technology over the last 5-years to understand and optimise submariner endurance for the technologically advanced future fleet of submarines. She has a special interest in optimising the performance and wellbeing of humans in complex human-machine systems.

N/A

In a world where complexity is the norm and certainty is rare, adaptability isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity. And when we combine it with empathy, structure, and a commitment to quality, we create programmes that deliver real, lasting value.

N/A

In a world where complexity is the norm and certainty is rare, adaptability isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity. And when we combine it with empathy, structure, and a commitment to quality, we create programmes that deliver real, lasting value.

Tim Curtis

Most transformation programmes fail—not because of poor execution, but because they never truly understood the race they were competing in. The BMT Strategy Canvas changes that.

Kathryn Walker

Coaching is a proven tool to support change leaders and their teams. The greatest impact and success has been achieved in transformation programmes, where structural and programmatic approaches are supported by attention to the cultural and behavioural aspects of change.